-C.S. Lewis

I wanted to begin my review of the latest Antietam book to hit the market with this quote for two reasons.

1. I love C.S. Lewis, and have a general rule of using his writing as much as possible.

2. While referring to philosophy, I think the principle of the quote applies to history as well. Good history must be written, if for no other reason, because bad history needs to be answered.

Which leads me to The Long Road to Antietam by Richard Slotkin, the latest in a long string of popular histories written to tell the tale of Antietam and the Maryland Campaign of 1862. The story of the campaign is, after all, one of the most important in American history. At the start of September, Vegas surely would have been giving good odds for Robert E. Lee and the Confederacy to win their independence, and soon. Federal forces in Washington were in disarray, Lee's army was riding a high tide of momentum, and it appeared as though Abraham Lincoln may never have the chance to issue the draft of the Emancipation Proclamation that had set in his desk since July. Yet, incredibly enough, just two and a half weeks later, Lee's army was limping back into Virginia, Federal forces had saved Washington, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, the North had new life, and Lincoln was issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. Surely, the Union general who led the Union Army of the Potomac has been heralded by authors like Richard Slotkin out of thanks to his contributions in saving the country....

This, however, is not the story Richard Slotkin tells in his latest work. This book is an attempt to tell the story of "how the Civil War became a revolution," as the subtitle reads. Antietam is a vital part of the story of freedom in this country. It was the battle that transformed the Civil War from being a fight to restore the Union to a revolution that would destroy slavery and establish a new standard of freedom for all Americans. In many ways, Antietam was a battle for the future of freedom in America. That is the story this book sets out to tell.

Granted, this work does have its strong suits. The prose is

highly readable and enjoyable, and its emphasis on trying to combine political

and military history is one which is sorely needed in the field of Civil War

scholarship. However, after reviewing the work, I can't really say that this work does much to benefit our understanding of the Antietam Campaign and George McClellan.

First off, the narrative is filled with numerous errors when discussing the history of Antietam and the Maryland Campaign. One of the most glaring errors that I found (on page 239) was Slotkin writing that the Roulette farmstead that was burned during the Battle of Antietam. The William Roulette farmstead was not burned during the battle. The Mumma farmstead was. Perhaps even the casual visitor who has taken the Antietam driving tour would be able to point this out, being that the Mumma farm is one of the 11 stops on the park driving tour, and interpretive markers discuss what happened to the farm. Certainly, the Roulette farm is near the Mumma farm, but mistakes like this simply should not make their way into print. The burning of the Mumma farm was an important landmark on the battlefield, and affected both troop movements and the lives of the Mumma family alike.

Another

error, this one repeated throughout the work, is Slotkin's assertion

that Lee's army was organized into a corps structure during the Maryland

Campaign. This is not true. In Maryland, Lee used a two wing structure for

parts of the campaign: one wing was ostensibly commanded by “Stonewall”

Jackson, and the other by James Longstreet. During the division of his army

under Special Orders 191, these two wings were divided up to accomplish Lee’s

objective. Slotkin argues that the Confederate corps structure increased the organizational cohesion of the Confederate

force; that was not the case. During the Battle of Antietam, units that were

supposedly in Longstreet’s “wing” were fighting under Jackson, and Jackson's men fighting under Longstreet.

Furthermore, it is not until a few days after the battle, once Lee was back in

Virginia, that his army adopted a corps command structure.

Other errors that can

be easily found include the claim that Union generals Fitz-John Porter and

William Franklin were actually arrested following their conduct at Second

Manassas (they had charges leveled against them, but neither was actually arrested).

Slotkin also suggests that George Meade was given the Pennsylvania

Reserve Division in the First Corps at the start of the campaign to improve its function as a

fighting unit. This is untrue; Meade took command of the division just a

few days before the battle when its prior commander, John Reynolds, was sent to

Pennsylvania to take command of the state militia. Slotkin also rather

strangely refers to the East Woods and the West Woods as the East and West

“Wood”. I could keep going for quite awhile, but you are starting to get the picture.

Despite these inaccuracies, my primary problem with Richard

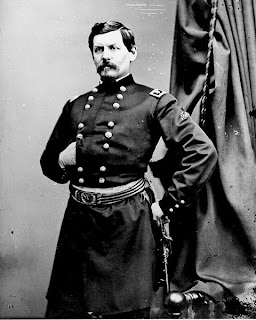

Slotkin’s newest book is the treatment of George B. McClellan.

DISCLAIMER: I am not a McClellan “apologist”. I am a Civil War historian who focuses on the Antietam Campaign, and one who thinks that discussing McClellan based on facts, evidence, and rational inquiry provides a more balanced view of the general, highlighting both his good and bad actions as a commander.

Now, back to the review.

Slotkin uses The Long Road to Antietam to describe George McClellan as arrogant, narcissistic, neurotic, devious, timid, incompetent, and altogether, one really bad dude.

Basically, he is Scar from the Lion King.

Each one is an evil character, intent on seizing power from the good guys (either Lincoln or Mufassa) and using it for their own nefarious schemes. Also, each one has facial hair, so, there is that too.

|

| George Brinton McClellan |

See the similarities, right?

Students of the Maryland Campaign are no doubt familiar with Stephen Sears, author of Landscape Turned Red, the most widely read book on the Battle of Antietam. Sears is well known as being very critical of George McClellan. Yet, despite Sears's harsh judgments on McClellan, even he believes it is beyond the pale to question the motives and sincerity of the general. As Sears wrote in an essay collection on the Army of the Potomac:

"Whether at headquarters or on the battlefield or in the political arena, in defeat and disappointment, George McCelllan never wavered in his determination to put down the rebellion. Historians will no doubt continue to debate his exact contribution to that cause, but they have no cause to deny the sincerity of his efforts." (Sears, "Little Mac and the Historians" in Controversies and Commanders, 24).

In The Long Road to Antietam, Richard Slotkin suggests throughout the book that George McClellan was a general more concerned with his political reputation and future than victory on the battlefield, coming close to, if not crossing the line of, accusing the Union general of treason numerous times.

Repeatedly, Slotkin argues that McClellan cared far more about his reputation in Washington than about the rebel army in Maryland. In fact, he suggests that the only reason McClellan wanted to achieve a victory in the Maryland Campaign was to stick it to Stanton and Halleck and to possibly rise to become the leading figure in the war effort once again. He singles McClellan out as arrogant and nefarious, leaving the reader with an impression of McClellan as a commander more interested in political intrigue than in affairs on the battlefield. In one of the harshest and most peculiar knocks against McClellan, Slotkin argues that the Union commander issued no written orders at Antietam to protect his reputation should the battle go poorly:

McClellan not only limited the forces he entrusted to his assault commanders, he did not fully inform them of the tactical plan for the battle they were about to fight. His refusal may have reflected, and been intended to conceal, his indecision about where and how to strike his heaviest blows. It is also possible that he refused to discuss his plans with his subordinates, and declined to issue written orders, so that no one—neither his colleagues nor his rivals—would know whether his plans had been well—or ill—conceived. His defensive position had to be impregnable on both fronts. (247)

Slotkin is arguing that McClellan did not issue written orders either because he was indecisive (with no proof or explanation as to why) or to protect himself from politicians in Washington (ie. Should the army lose,

his orders would not be used against him, with Washington being the second front referred to). This theory goes beyond the normal

complaints about McClellan being “slow” or “incompetent,” and ventures into the

realm of accusing the general of paranoia, and treachery. To suggest that McClellan would

put his soldiers’ lives at risk by knowingly holding back written orders simply to protect himself politically,

and to do so without any supporting

evidence is an egregious claim that does an enormous injustice to our understanding of both

George McClellan and the Battle of Antietam. Slotkin is no doubt not the first to make such accusations, but they are still misguided and incorrect.

Rather than Slotkin's arguments about McClellan's tactical decisions being motivated by political intrigue, let's have a look at the explanation for the lack of written orders put forward by historian Ethan Rafuse in what I consider to be the best book published about George McClellan at Antietam.

McClellan has been criticized for

not issuing written orders or providing explicit verbal guidance to his

subordinates laying out his intentions prior to the battle. This was a

consequence of McClellan’s desire—a commendable one given the unknowns he

faced—to maintain flexibility as the fighting developed and avoid committing

himself to a course of action that circumstances might prove unwise. (Ethan Rafuse, McClellan's War, 310)

Rafuse’s explanation of why McClellan did not issue written orders does not rely on an interpretation of McClellan as a psychotic general worried about his reputation in Washington over his troops in the field. Instead, it takes McClellan for who he was; a highly intelligent, competent, motivated, and loyal commander who realized that he was facing a fierce opponent in Robert E. Lee, and that the future of the country was in the balance at the Battle of Antietam. Thus, McClellan wanted to ensure that he would not be cornered into a plan which would become obsolete the moment the guns began firing.

Another major strain of Slotkin's critique of McClellan is that he believed that he, and ONLY HE, had the key to winning the war. This point brings up a few important questions.

Did Robert E. Lee drive Confederate strategy because he believed he knew what was best and how to win the war? Yes, and at a great and detrimental cost to the Confederacy. Lee's intense focus on the East, and on launching two aggressive invasions, cost his army crucial manpower and deprived the Confederate forces in the West of valuable resources and attention that contributed to the loss of the most important strategic points in the entire Confederacy.

Did Sherman believe that his "hard war" on Southerners was the only way to win the Civil War? Yes. He wrote voluminously to that effect. Did Grant believe that his strategy of driving toward Richmond in 1864 was the only way to defeat the Confederacy? Yes, and he pushed forward regardless of the chorus of cries in the North that he was a butcher wasting the flower of American youth on the fields of Virginia in a futile attempt to win the war.

The difference between McClellan and these generals is that he strongly disagreed with his superior in trying to carry out his strategy. Slotkin's argument that McClellan's belief that he alone knew how to win the war is misguided, as that was true for many officers. McClellan's difference is that he did not agree, or get along with, his Commander in Chief, where the other aforementioned generals did.

Historians must understand the disagreement between McClellan and Lincoln for what it was. Slotkin suggests that McClellan went so far as to foster a treasonous atmosphere in his headquarters, yet this was far from the truth. McClellan was true to the Union, and wanted to serve his country. He had political disagreements with Lincoln. He disliked Lincoln's strategy. He disliked Emancipation. As a result, he did not actively pursue Lincoln's goals for the war, which led to his removal from command in November of 1862. While McClellan's disagreements with Lincoln were not appropriate and he certainly deserved to be fired, there was nothing treacherous about this.

For those interested in a new and refreshing book on the Battle of Antietam, Abraham Lincoln, and George McClellan, The Long Road to Antietam is yet more of the same old McClellan bashing. It is a scathing indictment of George McClellan as a general, using errors and myths as evidence. Looks like the Merry-Go-Round of debate and controversy over George McClellan is still spinning away.

All things considered, you might be better off simply watching the Lion King.

Just being in print doesn't mean anything. As my grandfather would say, "Paper is patient. It lets itself be written."

ReplyDeleteWell said. I ordered this book right after it first came out several weeks ago. It sits unopened on my coffee table. More of the same. Few primary sources. A disappointment.

ReplyDeleteJim Rosebrock

Great review. I too was disappointed in the book. Slotkin relies almost entirely on secondary sources particularly Sears. Looking at the footnotes in the back of the book at least 65% reference Sears' books on Antietam, McClellan, and McClellan so-called Letters.

ReplyDeleteI see few references even to the ORR.